The Historic Bigfork Hydroelectric Project

PacifiCorp’s 4.15-megawatt (MW) Bigfork Hydroelectric Project (the Project), built in 1902 and located in Bigfork, Montana, is a historic resource eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. The Project exemplifies an early, small-scale hydroelectric power generating facility used to bring electricity to the local Flathead Valley. The historic development of the northern valley, and specifically the city of Kalispell as the economic and social center of the area, is directly linked to the Project’s ability to supply power to commercial and residential customers. This differed from other hydroelectric facilities of the time that only served the mining industry. Additionally, because the Project remains essentially unchanged since the early 1930s, the power plant architecture serves as a working model of an early twentieth century hydroelectric operation.[1]

The Project’s story begins in the Flathead Valley, a place within the traditional territories of the Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d’Oreille tribes. By the 1880s, non-Native Americans travelled to the Flathead Lake area via a long railroad, stagecoach, and steamboat trip originating from Missoula, Montana. Early settlement in the Bigfork area began during this time. The townsite of Bigfork was platted in 1901 by Evert L. Slither, Sr.

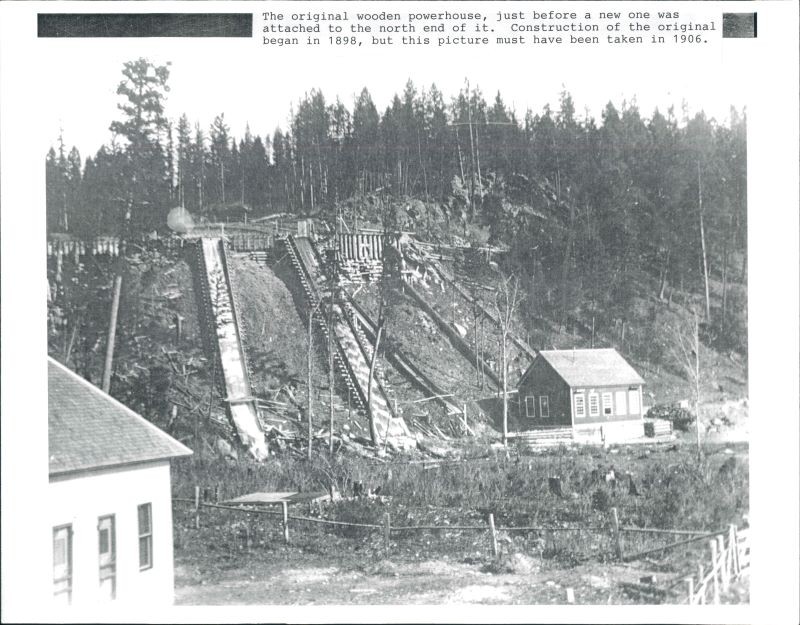

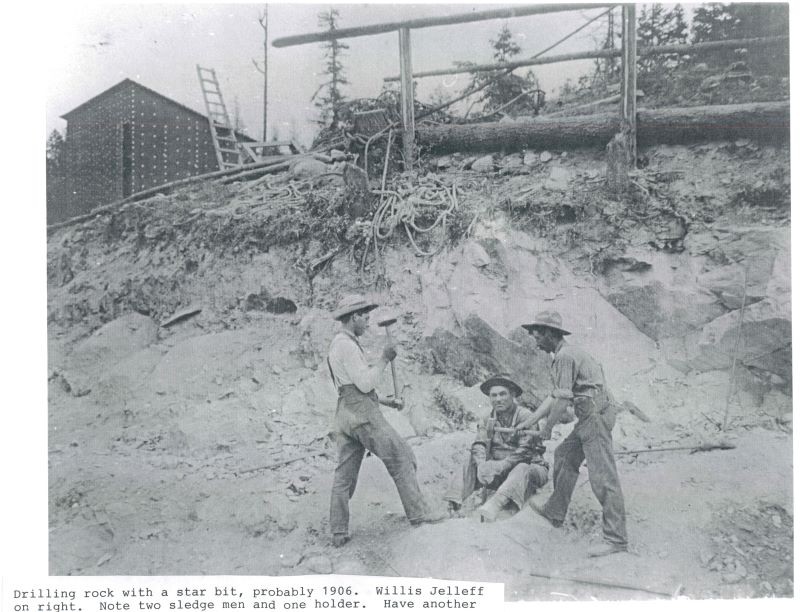

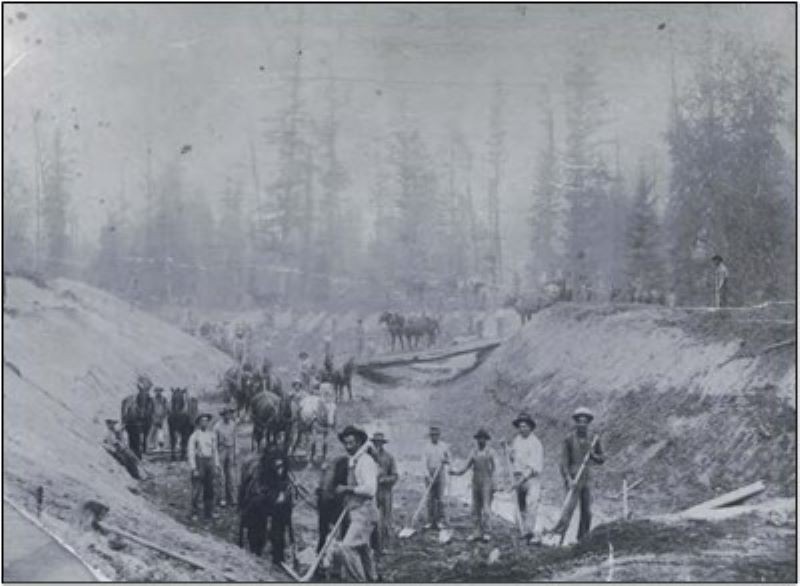

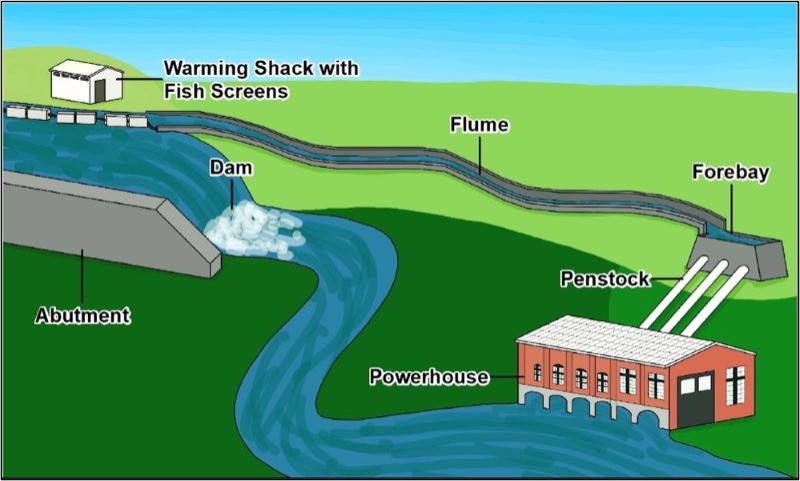

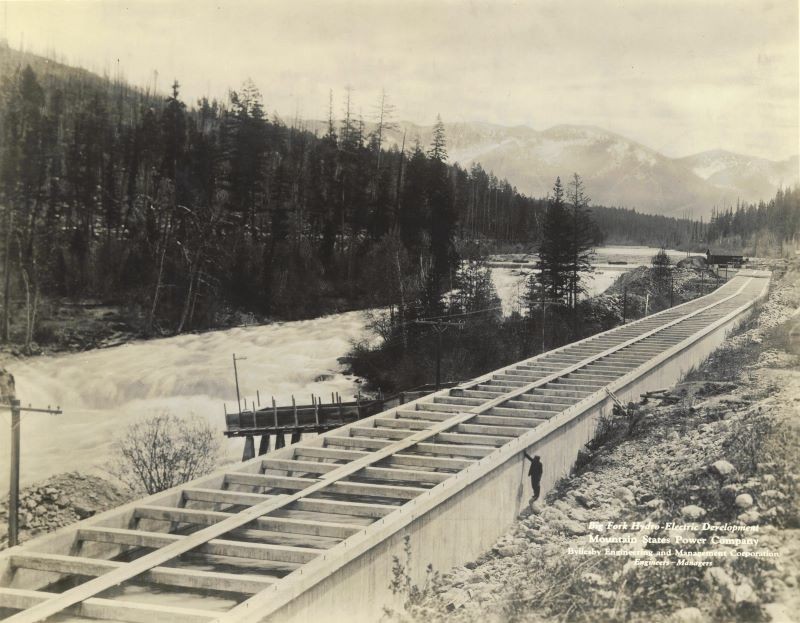

Development of the Flathead Lake area coincided with the electrical revolution experienced by the United States at the turn of the century. Between 1899 and 1925, electric-powered machinery use in the nation rose from 5 percent to an astonishing 70 percent.[2] Understanding the significance of hydroelectric power, Lafayette Tinkel and his son Frank filed for a water right on the Swan River in 1900 with the intent to build a hydroelectric facility. Tinkel and his employees hand dug a canal that diverted water from the Swan River to a wooden flume and ditch that carried the water over one mile to a forebay at the top of a steep hill, then down penstocks to a wooden powerhouse located on the south bank of the river. The Tinkels incorporated the Big Fork Electric Power & Light Company (BEP & LC) to fund construction, and by 1902, the facility was producing power.

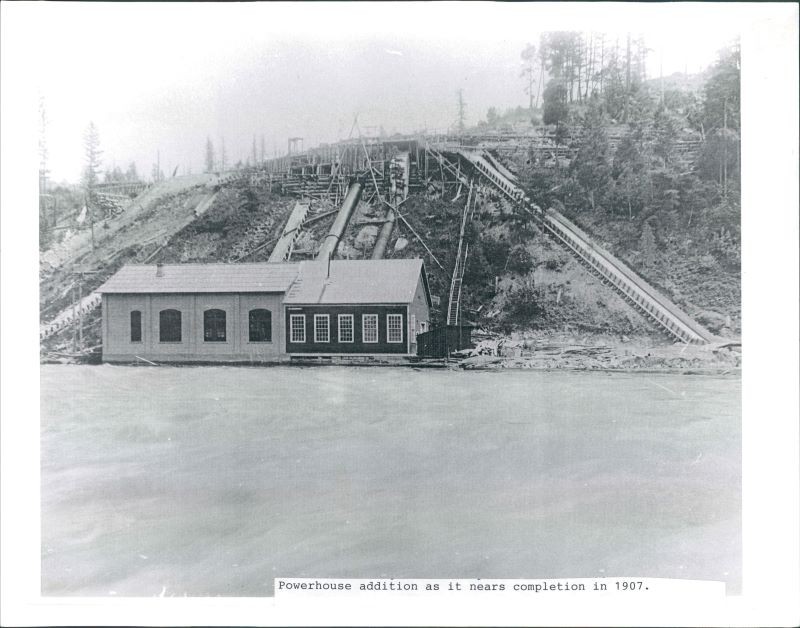

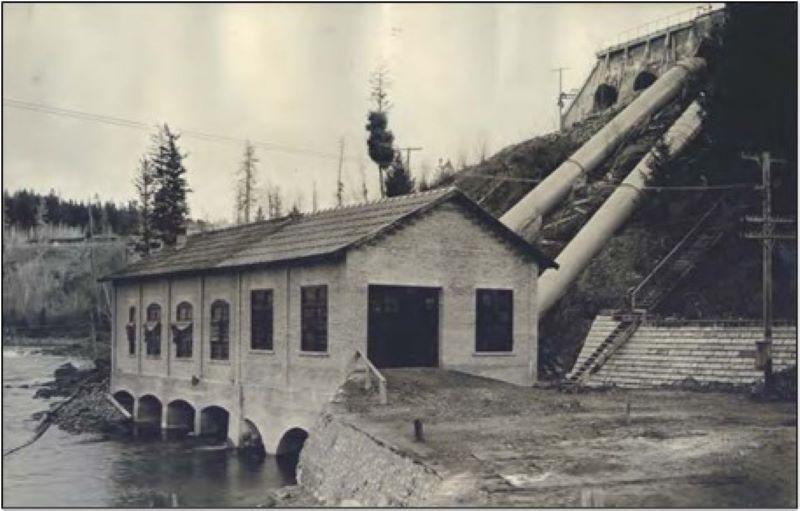

For six years, the BEP & LC plant operated as a small hydroelectric project, developing a minimal amount of the Swan River’s energy potential. To increase plant capability, an injection of capital was needed to update and construct new facility features. The needed funds became available in 1907 when BEP & LC sold their Bigfork facility to Flathead Valley Water Power Company (FVWPC). Construction work began immediately, and by 1910, a concrete diversion dam, new headworks, a reinforced-concrete flume, and a new brick powerhouse were built.[3]

Additional features included an underground wood-stave pipeline to transport water from the earthen ditch to a rebuilt forebay, and new turbines, generators, and transformers. By the end of 1910, the new turbines and generators could produce 1,250 kilowatts (kW) of electricity at the Bigfork facility, and three new transformers increased voltage from 2,300 volts to 33,000 volts.[4]

Ownership changes in the late 1910s sparked a second period of improvements at the Bigfork Project after Northern Idaho & Montana Power Company, an entity that previously absorbed FVWPC, went bankrupt. Ownership transferred to the Mountain States Power Company (MSPC) and upgrades began at the Project in 1924. The original wood-frame powerhouse, which served as an addition to the new brick powerhouse, was replaced with a new brick structure and the wooden building was moved to another location to function as a garage.[5] MSPC also removed an older generator and installed a Francis-type turbine and two 1,700-kW Allis Chalmers generators, one in 1924 and the second in 1928. With a total of three generators, the Bigfork Project’s capability increased to nearly 42,000 kW.

Increased power capability required additional developments at the Bigfork Project, and new transformers were installed next to the powerhouse. To accommodate headgates and penstocks for the increased number of turbines, the forebay was rebuilt again and the spillway moved and replaced with a reinforced concrete channel. Between 1930 and 1931, the dam walls were raised from a height of 4 feet to the structure’s current height of 12 feet increasing the rate of flow in the diversion canal to 700 cubic feet per second. Other structures constructed during this time include expanded dam abutments, a fish ladder, and a wood-frame building heated by a wood-burning stove. Known as the warming shack, this building kept staff warm while maintaining and operating headgates at the Bigfork Project during the winter months. A final improvement came about in 1936 with the construction of a concrete flume and lined ditch near the underground wood-stave pipeline to increase water flow to the forebay.[6]

In 1954, MSPC merged with Pacific Power & Light Company (PP&L) as the company could not produce enough electricity to meet the demands of their increasing customer base. PP&L immediately began construction of several new hydroelectric and coal-fuel generating plants in Washington and Wyoming to satisfy energy demands. Over the next 30 years, the company continued to grow and increase power capability at the Bigfork Project. In 1982, PP&L changed its name to PacifiCorp.

A few changes have occurred at the Bigfork Project since the second period of improvements in the 1920s and 1930s. The transformers were moved to a new substation south of the powerhouse, the original wood-frame powerhouse (re-purposed as a garage) was removed, remote actuation replaced manually operated controls, and high-density polyethylene pipe replaced the underground wood-stave pipeline after it collapsed in 2000.[7]

In addition to maintaining the historic features at the Bigfork Project, PacifiCorp stands committed to preserving, restoring, protecting, and improving both fish and terrestrial habitats for the conservation of native species within the 80-acre Bigfork Hydroelectric Project boundary.[8]

An example of PacifiCorp’s conservation efforts includes the installation of fish screens at the water withdrawal section of the dam to prevent fish entrainment. Fish screens were originally added to the bottom of existing metal trash racks that had been affixed to the concrete intake structure sometime after the 1940s[9]. A new screen system was installed in 2005. PacifiCorp recently determined the need to upgrade and automate debris cleaning of the screen/trash racks. In February 2022, the fixed fish screen/trash rack structure was replaced with self-cleaning traveling fish screens.

Because the concrete intake structure with trash racks is listed as a contributing resource to the Bigfork Hydroelectric Project, removal of this structure, and subsequent replacement with an electrically mechanized system, was considered an adverse effect to the site’s integrity aspects of design, feeling, and association. The addition of the modern, mechanized fish screens altered the Project’s original design and minimally compromised the site’s sense of feeling and association, attributes which allow the property to convey the historic character of an early twentieth century hydroelectric operation. To mitigate these adverse effects, PacifiCorp developed this webpage to provide information on the Project’s history and significance as an early, small-scale hydroelectric facility that brought electricity to the Flathead Valley and thereby facilitated the region’s successful economic development.

Another example of PacifiCorp’s commitment to both historic and environmental stewardship concerns the 2021 removal of contaminants from the Project’s transformer site where oil-filled transformers and other electrical equipment had leaked harmful PCBs, PAHs, and dioxins into the surrounding soil. In addition to removing the contaminated soils, PacifiCorp removed several structural components including a concrete pad with an interior oil-water sump, concrete footings, and concrete slabs supporting a second generation of transformers. These components represented character-defining features of the transformer site which is a contributing resource to the Bigfork Hydroelectric Project. Because of their historic importance to the Bigfork Project, removal of these components resulted in an adverse effect to the historic hydroelectric property. To mitigate the adverse effect, PacifiCorp documented the removal process with photographs and text describing the removal actions. These items will be included in the next revision of the Bigfork Historic Properties Management Plan.

PacifiCorp’s conservation efforts also extend to wildlife. In 2021, the company produced the Bigfork Hydroelectric Project Wildlife Conservation Plan, a document that discusses existing terrestrial wildlife resources, potential Project impacts to wildlife, and wildlife conservation methods.[10] As a transitional zone between the forested Swan Range to the east, and the Flathead and Swan valley wetland complexes to the west and south, the Project area serves as a travel corridor for large mammals including mule deer, white-tailed deer, mountain lion, black bear, and grizzly bear. Other animals observed in the vicinity include the coyote, red fox, river otter, beaver, mink, raccoon, and numerous bird species.

As a hydroelectric facility, the Project consists of several features with the potential to cause inadvertent animal mortality. To mitigate potential hazards, PacifiCorp maintains a forested habitat so wildlife disturbance from human recreationists can be reduced. Nesting platforms constructed near transmission structures allow eagles, herons, osprey, and geese to nest safely. In the event wildlife accidently fall into the 1,800-foot-long canal, an escape ramp constructed at the mouth of the canal allows for a safe exit.

The Bigfork Hydroelectric Project has come a long way since Lafayette Tinkel first put a shovel in the ground to excavate a diversion canal for his planned hydroelectric project. Over 100 years of improvements have enabled the Bigfork Project to currently generate up to 4.15 MW of electricity, a feat that amazingly still occurs on generator and turbine sets installed in the early twentieth century.

[1] Heritage Research Center, Ltd., Cultural Resource Investigation: Re-Evaluation of the Big Fork Diversion Dam, 2000, Missoula, MT, prepared for Black and Veatch, Kansas City, MO, pp. 18-20.

[2] Ibid., pp. 11-12.

[3] Matthew Sneddon and Heather Lee Miller, Bigfork Hydroelectric Project, FERC Project No. 2652, Historic Properties Management Plan, 2014, prepared by Historical Research Associates, Inc. for PacifiCorp, pp. 9-10.

[4] Ibid., p. 10.

[5] Ibid., pp. 11-12.

[6] Ibid., p. 12.

[7] Ibid., pp. 12-13.

[8] Summer Peterman, Bigfork Hydroelectric Project Wildlife Conservation Plan, August 2021, prepared by PacifiCorp, Portland, OR, p. 6.

[9] Letter to Pete Brown, State Historic Preservation Officer from Todd Olson, Director of Licensing and Compliance, PacifiCorp, dated July 21, 2021.

[10] Summer Peterman, Bigfork Hydroelectric Project Wildlife Conservation Plan, August 2021, prepared by PacifiCorp, Portland, OR.